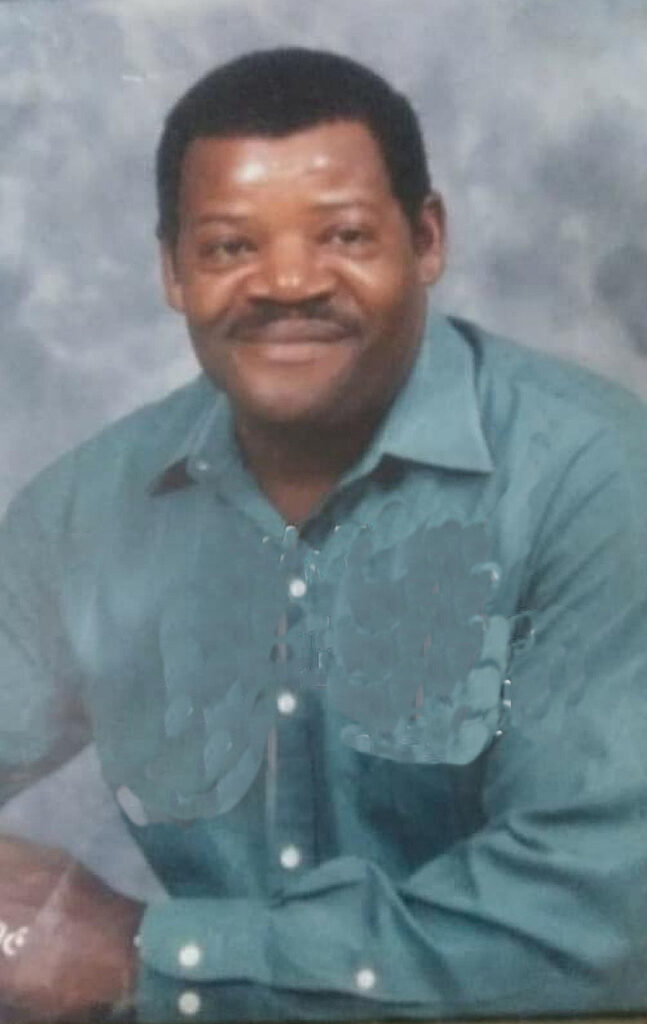

Peewee was nearly seventy years old now. As he invited me into the living room of his doublewide, it stood out to me that he moved more slowly, talked more slowly, was less energetic than the younger version of this man I had spent much time with years before. His son, not even thirty years old, had recently passed away. Peewee was hurting. That was the real reason for his slower movements and more subdued demeanor.

But he was still strong. Peewee had always been strong. He and his first wife, Mary, who had passed away years before, had seven children. For nearly twenty years they lived in a tenant house on my family’s farm and helped us on the farm, their family working alongside ours. My siblings and I grew up with Peewee and Mary’s kids.

We endured together the muggy hot summer workdays in the fields of southeastern North Carolina that built our character and took our strength. It seemed to me, though, that Peewee was always strong, no matter how hot the day or how hard the job.

But Peewee did have a weakness. Most weekends much of his very hard-earned money would buy him a bottle. Apparently, the strength we’d all seen in him through the long work week forsook him in his beginning-of-the-weekend money management decisions.

“Did you know your Mama was the reason I quit drinking?” Peewee said in our conversation that had turned from his recently passed son to my parents who had passed a few years before.

“No. I never knew that.”

“She was. One day I was working on a tractor for your daddy and your mama came out to the shop. She said, ‘Peewee I want to talk with before you leave today.’ I said ‘okay.’”

Peewee and I could always talk in an open-hearted way. He and his family were African American, and we had an unusual bond that accommodated our honest conversations about, among other things, racial issues, even personal ones that existed right there on our farm.

My dad had been a prejudiced man and didn’t always treat Peewee the best. Peewee could share his frustrations with me, and I mine with him. He’d had a lot of pressure, feeding a family of nine on the wages of a farm laborer, so weekend binges were his way of coping. (My dad came to Christ years after those days of our two families working together, and Daddy’s racial views improved drastically. One year Peewee’s family and ours celebrated Christmas together.)

“When I was leaving late that afternoon, your mama stopped me in the driveway. She said ‘Peewee, you know, you work so hard for your money, and we depend on you so much. But you can’t get ahead because you spend your money on alcohol. You and Mary could own your own home, and who knows what else you could achieve. But you can’t do it unless you stop drinking.’”

I had not known about that conversation. What I did know was that I was sitting in a house that Peewee owned, situated on a plot of several acres he had bought and built houses on for some of his children. I knew he had given so much money to his local church, which one of his sons now pastored, that they were able to build a nice sanctuary, in which Peewee and all his family gather weekly for worship. I knew this strong man who never could seem to get ahead was now financially strong.

Peewee looked down, fighting back tears. “I never took another drink.”

“I had no idea. Thanks for telling me that, Peewee.”

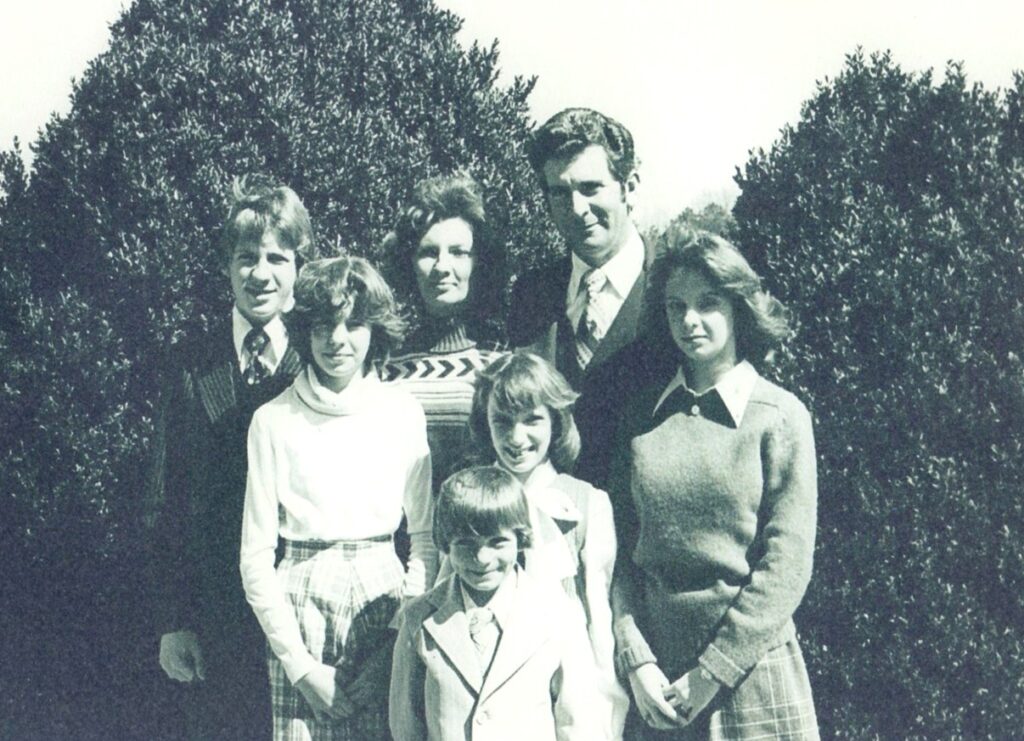

My mom was a quiet, gentle soul. She had to step squarely out of her comfort zone to speak to Peewee the way she had that day. She never knew the impact of her courageous words to Peewee. But he had obviously remembered them well.

Jesus said to not let our left hand know what our right hand is doing. If we apply that to the Body of Christ, we shouldn’t go around to the other members of the body pointing out the good things we’ve done.

If we each apply it to our own body, we should be willing to give and help without keeping a record of it, crediting ourselves as deserving of a reward for it.

When I was a kid working on the farm I would occasionally suggest to my parents that I be paid for my work “like the others who work on our farm,” I would say. My parents’ response to me was usually, “The work itself is your reward.”

I never made sense of that – that there was value for me in exhausting myself in the hot sun, my body becoming filthy and sore – until I realized years later that those days of work added intrinsic value to me, like work ethic, know-how, sense of accomplishment, and fond memories of working alongside family and friends.

My parents were teaching me, whether intentionally or not, the lesson of your left hand not knowing what your right hand is doing. “Just work well and let that be it” more simply put.

I have no doubt that many, if not all, who are reading this pour, and often, yourselves out without ever thinking what you deserve in return or of telling others so they’ll admire you for it. That’s the lesson of Jesus at work in your real life.

It was cool to learn what my mom did for Peewee some thirty years after she did it. She sowed seed she never harvested. Seed sown with fruit unknown to her.

Or is it? I don’t understand clearly how and when God gives rewards to His children, but I’m confident Mama either has by now received them or will soon receive them. She’s with Jesus now, not because of any good things she did in life, but because she trusted Him to be her Savior. He’ll decide how and when rewards are given. Our job is but to have our seed sown with fruit unknown.